Years ago, we posted in praise of poor production. This was my story more so than Robyn's (she started in 2002); but it remains the foundation for what follows. The amateur hobby is the life's blood of the industry; and it's where we want to stay...

But there was a time when it wasn't so easy. Sure, the hobby existed. But the tools? Not so much - or rather, not the same tools and not quite so easy. The creative spark was there from the beginning. If not, our gaming hobby might never have been. These games weren't birthed in a corporate boardroom. They were the stuff of enthusiastic amateurs who made their own fun and saw the potential in what they'd created. And the success of D&D inspired a cottage industry of small-press rulesets and zines. It's no different now; but looking back half a century, it was a whole other world, with far-reaching implications.

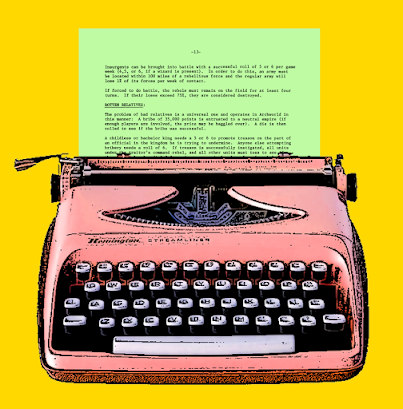

Imagine it's 1978. You've got ideas. You want to create. Maybe you want to publish, if only for local consumption, your own ruleset or fanzine or whatever. Home computers were available only to a limited few, and handwritten rules were out of the question. So you ended up dragging a typewriter down from the attic or up from the basement. It was the absolute state of the art back then, at least for home publishing. You clacked away at your manuscript, applied correction fluid (google it, kids), and made your semi-pro masterpiece. And it didn't stop there. Add artwork and maybe bindery, and there was still lots of work to do...

Maybe you did your own art. Cool! Or maybe you were lucky enough to have a talented friend to lend a hand. Alternately, your local library had plenty of public-domain art you could Xerox. I had an indulgent mother with a photocopier at the office. I'd leave space on my typewritten pages for artwork, copied what I needed, cut and paste the borrowed bits (and not pictures physically cut from the books, Heaven forbid) onto this, and finally, photocopied everything all over to get a delightfully amateur, semi-professional look. If the project was especially ambitious, I'd print the covers on colored card stock for panache.

This had material impacts on the way these products were approached and used. You couldn't just backspace and insert new sections. Major revisions meant starting all over, so you took care and avoided that. This probably resulted in shorter, sparer products. I'm convinced that old-school's open-endedness was only partly deliberate. It was surely aided by the labor intensity of production. There were entire worlds of imaginary space for the referee to wander in; and the lack of photorealistic art left more to the imagination. It was an emergent property of this approach - and one of gaming's genuine happy accidents.

Say what you will, but this is how our hobby began. And observant readers (that means you) have surely noticed how many of the products displayed along the right side of this page resemble what I've described, with a few nods to style, obviously. The early hobby's analog production made it an arts-and-crafts affair, but also a unique approach to play. One well worth preserving. For several years we've deviated into slicker production, and while I found it a worthwhile exercise, I've lately rekindled my love of amateur rulebooks. Anyway, the primitive look of these early games is by now iconic - and not merely a failure...

There was this guy back in the day who published his game using the above formula, complete with card-stock covers stapled down one end and slipped into Ziplock baggies for sale at the local hobby shop (he knew the owner). He sold a handful of copies and was ecstatic (he ran a local campaign, so was already a heavy hitter). This added to his celebrity and probably remains a cherished memory. Anyway, the budding hobby's analog mystique made his creative process personal - and like him, we feel extremely fortunate just to be here publishing homemade games and recreating our history. Long live the amateur hobby!

Superb explanation of old school simplicity.

ReplyDeleteFrom your old post: "The amateur nature of the artwork made it look, and feel, like something created by my PEERS. It was something I could make, which put me into the action. I felt like I COULD DO IT..."

ReplyDeleteThese last words are very important. Today I only feel as a consumer, fighting my way back to being a creator.

And the zine movement has been making a strong comeback! :-)

ReplyDeleteAstute observations, James. As always, you have a keen eye for what makes our hobby amazing.

ReplyDelete